By nature slowness is expansive, yet it allows us to hear up close.

Eliane Radigue

This is a collection of digital artifacts that inform and reveal the elaboration of a project which will eventually become a 22-hour broadcast, a single contribution among 99 others, as part of the collective 100-day broadcast project Radio Art Zone, which will take place from 18 June to 25 September, 2022.

You will find here a series of irregular dispatches, any of which may find a place in (or contribute behind the scenes to) the final result. Regardless, each is a node of research on the way to the realization of the finished broadcast. These accumulated fragments, various as they are, reflect the actual labor of the project, and they are intended to support it with supplemental and complementary material, providing a deeper and more detailed context.

The most recent dispatches appear at the top of the list, so scrolling down is the same as going back in time.

Twenty-two hours is an expansive canvas, an unpainted Sistine ceiling; an ocean, a national railway’s-worth of tracks and junctions. A solar system. An endless steppe. I set out to fill this void with a collection of slow dynamisms that indulge my long-standing fascination with what human attention undergoes when faced with endless plains, vast oceans, the wind and weather, the blur of travel, and the birds and stars above.

Visit Bandcamp to download this work as full-resolution 24bit-48k audio files. You can pay what you want, even nothing.

The full 22-hour broadcast is also available online.

Full Broadcast on Radio Art Zone

The full archived broadcast of the 22-hour radio composition Beyond sublargo, broadcast worldwide on 8 August, 2022, has recently become available on the Radio Art Zone website. You can use the player below:

Once we went traveling

once we went traveling

we were far away from home

i felt the curve of the earth under me

i felt the yawning distance

between me and home

i felt the land unscroll beneath us

as we traveled from place to place

i gazed out the window at the landscape

never forming a solid impression

once we went traveling,

i imagined strange things

i dreamed of a different life

i saw how things could be different

from what i was used to

Nicéphore

Perhaps he who is credited with the invention of photography is the most famous person to have Nicéphore as a given name; his surname — Niépce. The first photographically-created image, an acheiropoieton of science, can be understood as a success only from a technical point of view; the depiction, while ingenious, is neither precise nor beautiful:

But we can, on a whim, convert this arbitrary data into a raw file, and then redirect it to our sound file editor and open it directly. In this manner, characteristics from another dimension suddenly swing into view.

This is merely a curiosity, however, and no useful conclusions can be drawn from it.

The coming of light

❝ After a number of years of disuse, the sawmill was replaced by an electric generator to give light to the village school. And the local people, when told of the plan, did not believe it could happen.

‘How can it be? How can you get light out of the running water and the turning of a wheel? Water extinguishes light,’ they insisted.

And on the day the light was to be turned on, on that day the snowy hill before the school darkened with all the villagers, and all of those mountaineers from the area around who had heard the stories, all of then dressed in their traditional black clothes, who had come to witness the event.

First they were given the chance to touch the light bulbs, to see how they worked. They expected to find kerosene in them, but there was no kerosene.

‘Then how can they burn? There is just a little iron wire inside. It is not going to burn.’ They could not understand how the whole system worked.

So in the evening, when the water was let flow, and the wheel began to turn, and the generator began to work, and the electricity began to move through the wires, all of the rooms in the school suddenly lit up. And the local people were indeed astonished.

Unfortunately, I no longer remember the source of this story fragment; it was found among some of my old notes. But the audio is from the film The Last Ones – უკანასკნელნი (Aleqsandre Rexviašvili, 2006), a semi-documentary about the disappearance of traditional ways of life in the western Georgian region of Rača.

Industry of bees

In response to a recent post by Studiolum, Svaneti 1. Stones, detailing the context, history, and making of a single religious icon and its church, I wish to supplement his reportage with a morsel of my own. He and I visited the places he is describing in his ongoing series together.

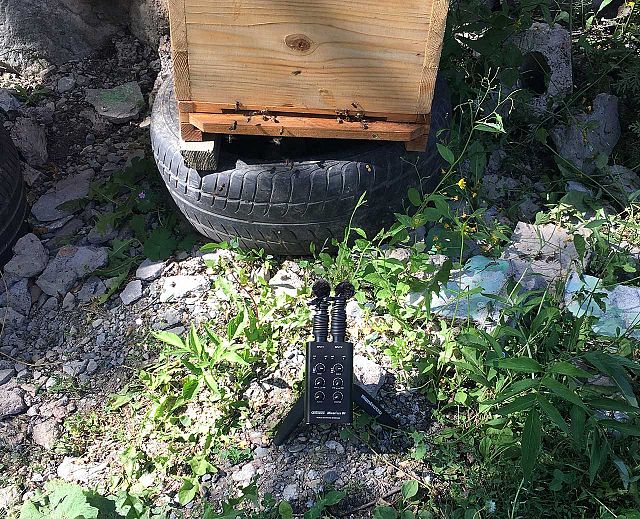

In the same valley of Latali, at Yenashi, there is the Monastery of St. Jonas, where the monks raise bees, which is not unusual. A small row of crude wooden box hives and an exuberant buzzing greets each visitor who passes through the gates. As a memento of the visit, I made this recording.

Although I am not religious, I am nonetheless affected by the enveloping sensorial effects of authentic religious spaces and rituals. I strongly associate bees with Orthodox Christianity. The candles bought and lit by the devout, consumed by sputtering flames sending whisps of black smoke upwards along with their prayers, are made of beeswax. The soft murmur when the holy text is read in the vast stone interior is reminiscent of buzzing. The coolness of the stone and the depth of its shadowy spaces evoke perhaps the atavistic sense of being in a cave. These distinct sensations fuse into a single experience.

Do you remember?

Do you remember when we were kids, the big house on the side of the hill, the broad green lawn, its four shade trees, one in each corner, the road and the ditch with tadpoles at the lower end, the field of corn across the road, and the train tracks across the field? And beyond that, the river with its steep dirt banks and its little islands of mud, cutting through the fields, ancient and glistening?

Do you remember the patch of moist brown earth in the shade of the great maple, where no grass would grow? The tire swing, the treehouse, just a platform of old planks nailed into the great Y formed where the trunk split into two main branches?

Do you remember the stump where you watched transfixed as your grandmother hacked the head off of a live chicken, and then waited patiently for the final spasm of its heaving lungs, so that, at long last, the being became a limp mass of meat for the Sunday dinner?

Later, did you think of what you had seen earlier, the life going out of a living thing, or did you revel in your young mind at the pleasures of the shared feast?

Do you remember the farmers in their little trucks rattling down the dusty gravel road, pulling behind them an ethereal plume of white dust, expanding after them like a squirrel’s tail, at length slowly dissipating in the stillness, until some unseen movement of air slowly swept it away? The passing truck was already long over the next hill.

You must remember the freight train that passed, almost everyday in the summertime, on those tracks at the other end of the field across the road. That if you called out at the man in the engine, at the top of your little child lungs, the magical phrase, "oo-ah-oo", sung in two notes of the pentatonic scale, alternating, up and down and up, like an Indian call. And then sing it again, and again, and also made a gesture with your little fist, like pulling something down from the sky.

Well, if the man in the train engine saw that, and heard you, then he would wave back at you with a smile, that you could see from across the distance, and answer your request. He would repeat your gesture as he went by, pulling down on the cord above his head that caused the train whistle to blow, jubilantly and sadly into the stillness of the summer heat, slowly fading away as it passed around the bend.

Grass: A Nation’s

Battle for Life

❝In 1924, neophyte filmmakers Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack hooked up with journalist and sometime spy Marguerite Harrison and set off to film … the migration of the Bakhtiari tribe of Persia. Twice a year, more than 50,000 people and half a million animals surmounted seemingly impossible obstacles to take their herds to pasture.

“The filmmakers captured unforgettable images of courage and determination as the Bakhtiari braved the raging and icy waters of the half-mile-wide Karun River. They almost froze when they filmed the breathtaking, almost unbelievable, sight of an endless river of men, women and children — their feet bare or wrapped in rags — winding up the side of the sheer, snow-covered rock face of the 15,000-foot-high Zardeh Kuh mountain.”

Oblivion

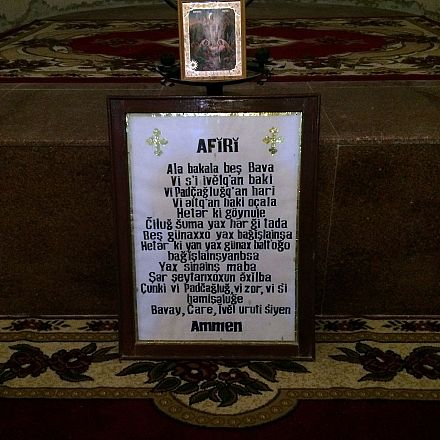

The small town of Nij (Qabala, Azerbaijan) lies on the cultivated lower slopes of the Greater Caucasus, well above where the foot of the mountains give way to the broad, less verdant basin leading east to Baku. A people called the Udi live here, one of the scattered remnant communities of a much larger Caucasian Albanian population that once inhabited the broader region. Udi, classified as a North Caucasian language, is listed as endangered by UNESCO, and once served, centuries ago, as the liturgical language of the Christian Caucasian Albanians.

During a visit to Nij in 2015, we stopped to ask for directions to the Church of Saint Elisæus, and we encountered an Udi man on the street, who offered to accompany us there. The church became a minor flashpoint in international relations in 2005, when, during a restoration project funded by Norway, a number of inscriptions of Armenian origin were erased.

Nowadays, there is a tablet with an Udi inscription displayed before the altar.

We ask the man, who speaks with us in fluent Russian, if he can read the Udi inscription for us. He struggles with it, and after the first few lines, he gives up. Between his school days and now, he explains, a new alphabet has been introduced for Udi, and he does not know it well enough to form the words.

“I never studied it in school, to be frank,” he apologizes. “Maybe later people will come here who can read it for you.”

Thanks to Tamás Sajó, and the patient Udi man.

Song of Grusia

Clara Rockmore, theremin viruosa, is accompanied by her sister, the pianist Nadia Reisenberg, in their rendition of a work by Rachmaninoff.

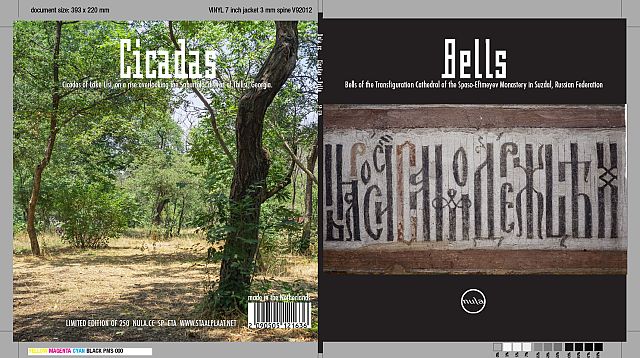

Cicadas

Cicadas is the title of a recent filecast, a field recording of the tree-dwelling insects made while traveling in Georgia. Soon after it was made public, I was asked by Geert-Jan Hobijn (Staalplaat) if I would like it to appear as one side of a proposed 7-inch vinyl release. I agreed.

For the other side, we have chosen a recording of the Bells of Suzdaľ, which I made during a performance of the bells of the Transfiguration Cathedral Spaso-Efimeyev Monastery in that Russian town, a few hundred kilometers northeast of Moscow.

The 7-inch vinyl release Bells will appear sometime in February 2022 on the Staalplaat label. Thanks to Geert-Jan Hobijn.

Song for a

dwarf planet

Pity poor Pluto: Demoted from its regal perch, the most distant planet in the solar system, a post held for the better part of a century. Aloft in its stately procession around the sun, in and out of Neptune’s orbit, to our eyes, it is not even a dot of light in the night sky. It is only through instruments that we know it is there.

Listen to the ringing in my ears. Everything we know comes to us through a few openings in our heads and our sense of touch. My head contains the entire universe, what little I know of it. That tinnitus then is the music of the spheres.

The working title for the composition that was to become A thinking ocean was dreamt up well in advance. As was, it now turns out, one of the main source recordings, made during a visit to Berlin some five years ago. We came across an man on the street standing alongside a similarly-old crank organ that played the waltz popularly known as An der schönen, blauen Donau. He offered us the chance to turn the crank. While my friend ground out the fusty tune, I made this very brief recording.

It lay on my hard drive, unperused, unused, literally for years before I found it again, and idly began running it through various processes, just because. From there, it multiplied into variations and is now the source for the main instruments on four of the tracks on the finished album. In the process, the title Song for a dwarf planet was dropped in favor of A thinking ocean as a tribute to Stanisław Lem.

Thanks to Tamás Sajó, and the anonymous crank-organ man.

Bells of

Krasná Hora

An autumn weekend in the Czech countryside, morning dew on the grass, frost on the apples, a small village in South Bohemia called Krasná Hora. You are given the keys to visit a baroque wooden bell tower (16th C.) on your own: a rare opportunity to see and touch and hear some large and substantial bells up close. But what can you do up there, without causing undue alarm to the people of the town?

So you proceed cautiously to tap the metal with your bare knuckles. The metal responds, invisibly, softly, and the minuscule mechanical distortions produced by your small, repeated pressures bring forth a call. Quietly, the bells begin to sound in thanks for your feeble efforts. Each bell in turn, Svatojan, Poledník, Prostředník, are probed with the recorder placed in its throat, the inner sanctum of its resonance.

In this mix of the recordings, I have partially layered the tone of the three bells to give an idea of the overall harmonic composition of the three sounding together.

Thanks to Dana Recmanová.

First marks

The first words one writes on a new, blank page take on a momentous quality. First impressions are often thought to be lasting, and it is well to carefully consider them. Each word, when solitary or nearly so, carries an added importance as it sullies a white snowfield with its stains. In each written gesture, therein lies a sacrifice.

Those first words one writes are important enough, that often one will practice them beforehand, out of public view, with a quivering hesitancy, on a loose and discardable leaf. One needs a place to consider each of these tiny commitments, before transferring them over to public view.

I feel something like that in beginning this online chronology for the work-in-progress that will become Beyond sublargo.

As the words coalesce into a mass of text, each word is demoted to a supporting, rather than starring, role. Each of the words, and then each of the posts, added to this collection are additive and supportive as opposed to emphatic or complete. I set off hoping that somehow this accumulation will eventually embody more than the sum of its parts.

Now on Bandcamp : the Album